It’s good epistemic practice to flirt with worldviews that are different to your own; to suspend disbelief and look around at the world through their lens. In this spirit, I read Reid Hoffman’s Superagency.1

Reid Hoffman strikes me as a very smart and reasonable guy. He’s very optimistic about AI, and is doing his part to accelerate AI progress as co-founder of Inflection AI, board member at Microsoft and investor in lots of AI companies via Greylock Partners.

While Hoffman wants AI progress to accelerate, it doesn’t seem to be “at all costs”. He seems to support some kind of regulation (though what exactly isn’t clear, as we’ll see), thinks robustness and safety work is important and has made sizeable donations to support work on AI safety (e.g. via The Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence).

Superagency is where Hoffman fleshes out his views on AI. He makes the case that AI will usher in an era of "superagency" where artificial intelligence amplifies human capabilities rather than replacing them. Hoffman argues that we should embrace a "techno-humanist compass" and pursue iterative deployment of AI systems, learning as we go rather than pausing development out of fear (man, he really hates the idea of pausing). His central thesis is that AI's future isn't predetermined but will be shaped by the choices we make today, and the best way to prevent bad outcomes is to actively steer toward better ones through innovation rather than prohibition.

I wrote up some more notes and thoughts on the book. A note on these notes: I listened to this as an audiobook, and didn’t have the time to carefully find quotes and copy them over. I might misquote Hoffman at times, or paraphrase his views quite roughly. I’ve tried to find the real quotes where I’m more critical.

Things I liked

Hoffman argues that one way the course of AI development has gone well (intentionally or otherwise) is that most AI today is something we choose to use rather than something used on us. Plausibly, AI could’ve been kept in the hands of a few powerful groups who could’ve made search algorithms or face-recognition tools or government databases much better without the public’s consent or involvement. Instead, the very best AI models are currently available to anyone who can afford it, and we get to (mostly) choose when to use them. That might change, but I agree with Hoffman that the wide accessibility of AI is currently a good thing, and probably a contingent fact about the world. Later in the book, Hoffman expands on this point; if a large proportion of the populace has access to AI and understands its benefits and limitations, that can lead to a wider conversation about how we choose to use it and regulate it. More usage means more buy-in and more consensus.

Hoffman talks a lot about how AI can help us navigate the overwhelming amount of information in the world. A mind-boggling amount of words, ideas and data is available to us, the news cycle is relentless and social media makes this all the more overwhelming. Recently, we haven’t had the tools to make sense of this, but AI can act as a conduit, helping us navigate information overload and harness all of the information to make useful progress on important problems.

Hoffman is bullish on using LLMs to help more people access mental health services. He rails against what he sees with our obsessive focus on what could go wrong with AI, and how this focus neglects what could go right. The status quo when it comes to mental health—increasing demand, overwhelmed services—is not something we should accept, Hoffman argues, and AI could help solve it. He’s excited about LLMs being used for therapy, but also LLM-assisted therapy and therapists using LLMs to better serve their patients. I agree with this overall take; LLMs can probably provide at least decent mental health support now, and likely soon something as valuable as actual therapy. Better mental health is good, let’s make it happen.

Hoffman is an advocate of Big Tech, and believes most people underappreciate the amount of consumer surplus most big tech companies provide. He cites a survey which found that people would rather pay $48 than give up facebook for a month. The same researchers found that users would rather pay $8,414 than give up emails for a year, $3,648 for maps and a whopping $17,5302 for search engines. I’m skeptical of these numbers, but I found this overall pretty convincing. As much as I hate ads, and probably other things that the big players like Meta and Google do to make money, we are getting an immensely useful service without any direct financial cost. I don’t recall how Hoffman ties this to the conversation about AI, but I’d guess he’d argue that AI companies are on track to do something similar, namely offering an extremely valuable service at a price that most people are very happy paying.

Things I did not like

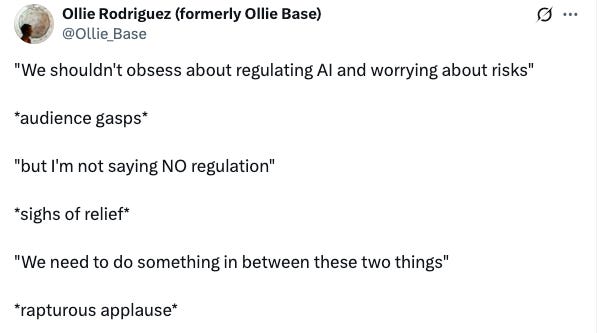

I found it hard to follow Hoffman’s views on what kind of regulatory infrastructure he thinks might be appropriate for AI. The below tweet, I can now reveal, was a jab at Hoffman, specifically this video from one of Hoffman’s lectures.

In one part of the book, he describes how much easier technology has made long-distance travel. At the turn of the 19th century, a journey across America was a harrowing, often life-threatening months-long endeavour. Now—thanks to cars, and gas stations and highways and cafes and mobile phones and credit cards—it’s a largely safe, painless, even pleasant hours-long journey. Hoffman points out that the safety infrastructure behind this technology is necessary. The journey is largely safe because there are speed limits, seatbelts, payment security, stop signs and traffic lights. Hoffman is keen to point out that, when we first developed cars, it would’ve been a poor choice to limit their speed to under 25 mph or put speed bumps every 100 metres. That would’ve massively limited their usefulness and impact on the world, and therefore our prosperity.

And so it goes with AI. AI can make us more productive, happier and healthier, and we shouldn’t slow it down or pause. We just need some good, modest, unimposing regulation (or measurement, or meaningful conversation). Right?

But Hoffman leaves out what this might look like. He favours iterative deployment—AI companies releasing models, getting user feedback, using that user feedback to spot weaknesses and safety issues, and then iterating.

This seems like a reasonable first pass on the kinds of minor safety issues that might affect users, but Hoffman goes further and claims that the more rapidly we iterate, the safer AI will be:

“Rapid development also means adaptive development, and adaptive development means shorter product cycles, more frequent updates and safer products. You can innovate to safety much more quickly than you can regulate to safety.”

This strikes me as a strange claim. Adapting and updating seem like necessary steps for safer AI, but a slower pace of adaptation surely favours safety, even if it isn’t the best approach all things considered.

Consider the implications of Hoffman’s claim if we reverse it: slower development means longer product cycles, less frequent updates and … more unsafe products? So, the more time AI companies have to spend investigating safety issues, the worse they will do at fixing them? This can’t be true. Does Hoffman think that if governments built highway infrastructure faster, we would see fewer road accidents? Does he think that if nuclear weapons were easier to build, we’d be in a safer world, because major powers would “innovate to safety”?

Maybe I’m misunderstanding his view. Maybe agile, fast-moving companies are able to build safe and reliable products more quickly. Maybe he’s smuggling in race dynamics here, and thinks that if American companies build better AI faster, that would be better for the world. If that’s the case, he should spell that out.

Some other nitpicks I have about the book:

He pushes a nuanced version of technological determinism. As technology comes along, its impact is somewhat inevitable. We ought to embrace it and harness its impact. He cites mobile phones and electricity as evidence of this, but seems to neglect disanalogies like cloning and nuclear weapons; technologies where coordination has prevented or slowed proliferation.

Hoffman complains about the inconsistent commentary on AI and its impacts. In 2023, people were worried about existential risks from AI, he writes, but now they’re saying AI is all hype! This seems like a fallacy (a “now they say” fallacy?). Different people say different things at different times.

Hoffman argues that it was the right call not to impose too many safety regulations on cars as they were popularised, because cars are so useful. I’m not confident about this. Over a million people die from road deaths every year, and I expect many of those are preventable without compromising the impact of cars. Millions of deaths could’ve been prevented if we’d imposed lower speed limits earlier, built safer roads or forced car companies to figure out how to reduce injuries and deaths in crashes sooner. Our approach doesn’t seem like it was optimal, and I wouldn’t be surprised if, over time, we consider the fast rollout of cars and slow rollout of road safety measures to be reckless and a needless waste of many innocent lives.

He talks about race dynamics between the US and China and the “US lead” with little nuance, but also insists that the race to build AI is more analogous to the space race than an arms race (because AI already involves lots of testing). He seems to imply that AI is extremely important in the context of geopolitics and the future of civilisation, but also that we needn’t interfere with the trajectory of this nascent industry, at least not yet. There’s a tension here.

Co-written with Greg Beato, but seems to represent Hoffman’s views primarily.

This number strikes me as implausibly high. I find it hard to believe that the average person would give up a sizeable portion of their income before losing access to a search engine. Many jobs don’t require search engines, as useful as they are.